By Lisa Cooper, Ebbets Field Flannels

Larry Doby was called many things during his outstanding career: barrier breaker, pioneer, captain, All-Star, manager, executive, Lawrence, LD, and #14 amongst less honorable mentions from some less honorable men. True to style, Doby played through it all with his signature skills, grace, and focus.

Known as #2 to Jackie Robinson’s #1 when thinking in terms of breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball, what people tend to overlook is that Larry Doby was first in a number of instances pertaining to the breaking of the color line.

Doby was first Black man to play in The American League. He was the first to get paid to play in the Majors. While Jackie Robinson did not see any financial gain at signing and was sent to The Montreal Royals for a season before joining the Brooklyn Dodgers, Doby, upon signing his contract with the Cleveland Indians, received $5,000 with another $1,000 due to him 30 days later. Doby, along with Satchel Paige, shared in being the first Black men to win a Major League Baseball World Series.

On July 4th 1947, Doby hit his last home run for the Newark Eagles. July 5th he was playing for the Cleveland Indians. The very next season, 1948, Doby was instrumental in helping the Cleveland Indians win the World Series.

Born to a semi pro baseball player/horse-dresser father who fell in love with Larry's mother when he saw her rounding the bases in a baseball game on the street in front of her home. They married and soon enough young Larry, the natural born athlete, was lettering 11 times over on varsity squads in football, basketball, baseball and track. The summer of his high school senior year found him playing basketball and without giving it a thought, possibly not even knowing, breaking the color line in basketball while playing for the Paterson Crescents of the American Basketball League, a precursor to the NBA.

Doby was so good at basketball (earning scholarships for his skills) that he didn’t give baseball much notice other than that it was fun and he was good at it.

That same summer, between high school and college, Doby was paid $300 to play second base for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League. He played as Larry Walker, an assumed name adopted in order to protect his amateur status, so as not put his upcoming basketball scholarship with Long Island University in peril.

Then the Navy called. Doby had no choice in the matter. He was drafted. He asked to be placed in the Marines, but the answer was no. He was to be in the US Navy as a physical education instructor.

While Doby didn’t see action in battle, he saw much of it on court and on-field playing for The Great Lakes Naval Station in basketball and baseball. Word had already been spreading about Doby's game. Once he started playing in the military (being stationed and playing with other pros) the scouts, coaches, and owners became fully aware of his skills.

After his discharge from the Navy in 1946, Doby signed a contract to play Winter-ball for the San Juan Senadores of Puerto Rico in 1947. Come spring, he resumed play with the Newark Eagles, helping take the win in the Negro League World Series.

During his career as #14 with the Cleveland Indians, Larry became a 7-time All-Star center fielder, and, as mentioned above, won the 1948 World Series. Doby helped Cleveland win an American League record of 111 games as well as the AL pennant in 1954.

Doby went on to play for Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers, and in 1962, was invited to play for the Chunichi Dragons in Japan. President Kennedy got wind of the impending deal and called Doby to the White House. He told Doby that his playing baseball in Japan could help strengthen goodwill and relations between the US and Japan, and that Larry was representing not just the US, but also JFK himself.

After retiring from play, Doby became a scout, minor league instructor, and batting coach for the for the Montreal Expos. He then managed winter league ball in Venezuela for five seasons. In 1974, he became the first base coach for the Cleveland Indians, and finally becoming manager of the Chicago White Sox in 1977.

Retiring from baseball in 1979, he served as director of communications and director of community affairs for the New Jersey Nets of the NBA.

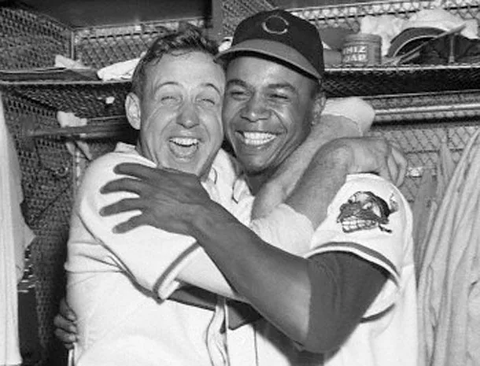

As best friends and neighbors, Larry and Yogi Berra spent time together almost every day at each other’s houses or down at the local American Legion post, talking about baseball, the Navy, and who knows what else. Later, In tribute to his dearest friend, Yogi Berra dedicated a wing of the Yogi Berra Museum Learning Center to Larry. This is where Larry Doby's memorabilia is housed.

In 1998, Ted Williams called Doby to let him know that he was to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. The words Larry crafted for his acceptance speech brought forth a standing ovation:

“You know, it’s a very tough thing to look back about things that were probably negative. You put those things on the back burner. You are proud and happy that you’ve been a part of integrating baseball to show people that we can live together, we can work together, and we can be successful together.”

Sage words for the ages by Larry Doby, #14.

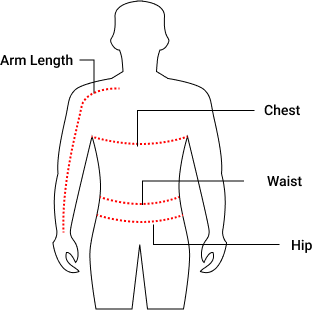

We are excited to bring you a limited edition ballcap featuring Larry Doby's #14 and his signature. Made with the same style and construction of our classic vintage wool ballcaps, this cap is built to last a lifetime.

6 comments

There was a lot more to him than being the 2nd man behind Robinson to integrate baseball. He gets a lot less fanfare but is very important in the story of America. Plus, the AL and NL didn’t play interleague then. So, it was similar but different for Doby in those ballparks that had not yet seen a black player. For him he was the true first in that league (AL). So maybe they were BOTH the first to integrate,but,Robinson came earlier on the timeline. But, making it no less difficult for Doby. I am glad you are recognizing and shining light on this integral man. :)